In relationship with Survivors and Missing Records

You have a right to ask for your family’s data back.

Boozhoo News River Readers,

We were quiet here last week and for good reason. Our team stepped away from screens to gather, learn, and reconnect in person with what grounds our work. After five beautiful days in lək̓ʷəŋən Traditional Territory, we're back - rooted in our purpose and ready to build together.

Thanks for being here, and on to the news!

This week’s stories include:

A story about Indigenous perspectives on marine stewardship: “For me, working with the ocean is about relationships and responsibilities, not just data.”

How Indigenous solutions to the climate crisis are systems of care - deeply embedded in relationships with land, water, and kin.

“There’s almost no data on how these tools impact nurses.” A U of T Engineering researcher assesses how AI tools support nurse workflow in First Nations communities.

Support Senate approval of Missing Records, Missing Children

The big picture: Indigenous peoples continue to lack complete and timely access to historical records about Indian Residential Schools, despite legal obligations for those documents to be turned over. The Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples report, Missing Records, Missing Children, highlights the barriers to locating, accessing and reviewing records that may contain key information about the lives and deaths of Indigenous children at residential schools.

Why it matters: Those barriers include a lack of information on where records for an Indigenous child, family or school are kept, and lengthy delays in accessing federal records. The report makes 11 recommendations, including that the federal government support and fund Indigenous-led approaches to locating and retrieving records across multiple jurisdictions.

Key points:

The recommendations reflect the principles that Indigenous peoples should have ownership, control, access and possession of records that relate to them (OCAP).

The obligations to remit documents are set out in the 2006 Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement, and parties are required to submit relevant documents to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

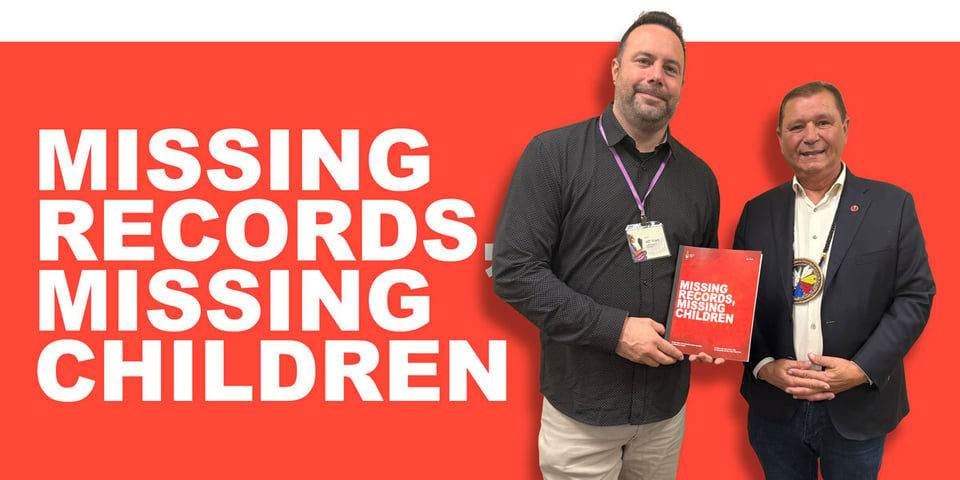

Animikii CEO Jeff Ward spoke with Senator Brian Francis at the Survivors Gathering in Thunder Bay this week. This report has not yet received Senate approval - so we’re sharing it today to help amplify the years of ongoing advocacy and help get the word out.

What they’re saying: “It is unacceptable that Indigenous peoples continue to encounter so many barriers to accessing records related to the lives and deaths of our children at Indian Residential Schools. Canada has a duty to honour this history and address the lasting impact of residential schools on Indigenous communities. To properly do so, the federal government must urgently ensure we have complete and timely access to all relevant records, as well as the funding and support necessary to lead this difficult and emotional work.” - Senator Brian Francis, who served as the Chair of the Standing Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples from December 2021 to January 2025.

“To the government these are ‘documents’, ‘files’ and ‘records’. Named after the manilla folders they used for years in an attempt to control and document our every move. To us: this is testimony. This is Truth. These so-called ‘files’ need protection well beyond what a filing cabinet in the bureaucrats office in Ottawa can offer: a place to honour their sacredness.” - Jeff Ward

Learn more: Read all 11 recommendations here and share with your networks.

Curated Articles:

The ocean as a living relative: Indigenous perspectives on marine stewardship

What happens when you stop seeing the sea as a resource—and start seeing it as family? For two Indigenous members of Oceans Network Canada, this shift isn’t just philosophical—it’s essential for survival. Wylee Fitz-Gerald learned her love of the ocean from her father, and it’s something she’s keen to pass on. “Through my studies, I realized that reconciliation needed to be part of my work, and I began a personal journey of reconnecting with my culture,” she said. “At Ocean Networks Canada, I’ve been fortunate to be supported in bringing those perspectives into my role, whether that’s advocating for Indigenous data sovereignty, speaking about partnerships at conferences, or helping colleagues understand Truth and Reconciliation. For me, working with the ocean is about relationships and responsibilities, not just data.” For her, this work is intensely personal. “When I work with students and communities, I see it as a process of co-creation, where we’re all learning and growing together. One of my favourite experiences was on a Mi’kmaq-led expedition in Newfoundland in 2024, where I met a student named Esmee. She reminded me of myself at that age, and later told me I inspired her to become an oceanographer. That moment reinforced for me why representation matters, and why we need Indigenous women’s voices in ocean science.”

LaShawn Murray (MIE PhD student) is working with four pilot sites near Calgary and Edmonton to evaluate how AI scribes are integrated into clinical workflows. In remote or underserved Indigenous communities, nurses are often the first — and consistent — point of contact for primary care. With less frequent physician visits due to demand or shortages, nurses play a critical role in delivering day-to-day health services, including chronic disease management, homecare and emergency response. “What’s different in OKAKI’s case is the focus on nurses and homecare professionals, rather than physicians working in hospitals or specialty settings,” says Murray. “There’s almost no data on how these tools impact nurses.” As part of her dissertation, Murray recently began visits to four pilot sites in First Nations communities near Calgary and Edmonton. She’ll evaluate how the AI scribe is integrated into clinical workflows, assess the quality of the generated notes, and explore its effect on provider–patient interactions.

Uniting Indigenous Women in Industry: Global Summit to Take Place in Vancouver in September 2026

Indigenous women leaders from around the globe will gather in Vancouver, British Columbia on September 28-30, 2026 for the Indigenous Women in Industry (IWI) Summit Canada, a transformative event designed to foster economic, cultural, and social opportunities for Indigenous women across the Indo-Pacific region and beyond. Hosted at the Hyatt Regency Vancouver on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy ̓ əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱ wú7mesh (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil Waututh), IWI 2026 will bring together over 250 Indigenous women and allies from Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Australia, and other international partners. The summit will focus on entrepreneurship, leadership, innovation, and next generation matriarchs, while strengthening global Indigenous-to-Indigenous connections and advancing reconciliation. The event is co-led by Rise Global, a 100% Māori and Indigenous-owned organization from Aotearoa, and the National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association (NACCA), Canada's national organization representing a network of over 50 Indigenous Financial Institutions.

The Future Has Always Been Here: Indigenous Solutions to the Climate Crisis

In a time when “green tech” comes with high-cost startups and extractive industries dressed in eco-branding, a quieter revolution is taking root. Drawing on generations of ecological intelligence, Indigenous innovators are building new tools that speak not only for survival, but for the sovereignty and well-being of future generations. From solar-powered water purifiers to permaculture designs that restore degraded landscapes, Indigenous technologies are blossoming all over the world. But these are not temporary fixes or market-driven products built to appease investors. They are systems of care that are deeply embedded in relationships with land, water, and kin. In Canada, there are over 1,700 Indigenous-led renewable energy projects transforming the energy landscape. By integrating traditional knowledge with modern technology, these initiatives not only address energy needs. They also reinforce cultural values. One notable Indigenous-led project is the Three Nations Energy Solar Farm in northern Alberta.

Qikiqtait exhibition reveals unique biodiversity and culture of Nunavut’s Belcher Islands

A new Inuit-led exhibition that transports visitors to the Belcher Islands, a unique archipelago in Hudson Bay, opened September 26 at the Canadian Museum of Nature (CMN). Visitors will learn how the Sanikiluarmiut (people of Sanikiluaq, the main community in Qikiqtait) have been working to develop monitoring programs and Inuit-led conservation to take care of the islands for future generations, by combining Inuit knowledge and modern technology. A key component of their innovative approach involves SIKU: The Indigenous Knowledge App, a mobile app and web platform developed by and for Indigenous communities. It provides land users with tools and services to support safe travel and knowledge transfer while empowering communities across the North to run their own projects, supporting self-determination and Indigenous data-sovereignty. Individuals can post about wildlife, sea ice, climate and other activities using their own language and knowledge system indicators to classify their observations. Data shared to the Qikiqtait project on SIKU demonstrates a compelling case study of Inuit knowledge and observations. These are used systematically and quantitatively in support of Sanikiluaq’s self-determination to take care of their wildlife and environment for future generations.

Add a comment: